Psychology in Action, And an Interesting Asset Class

One of the most fascinating and promising parts of finance research is a discipline called “behavioural finance”. It represents an important step forward in our understanding of how capital markets function, how risk is priced, and why certain inefficiencies persist and enable those who are disciplined to capture excess returns.

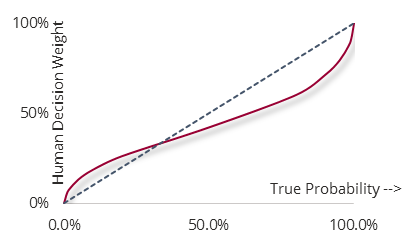

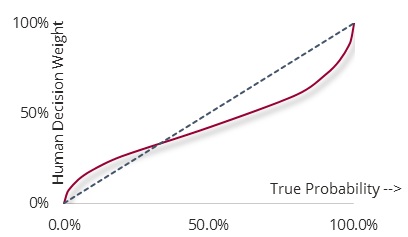

One such inefficiency evolves around how most people – and investors are also people – deal with probabilities. Research has repeatedly shown that humans tend to over-estimate small probabilities and under-estimate large probabilities (Exhibit 1). The reliability of this fallacy has given rise to two entire industries – gambling and insurance!

To be fair, the case is clearer in the case of gambling. The price of a lottery ticket is about twice what you’d expect to receive, on average, if you could play an infinite number of times. In the stock market, there is gambling too: it has been proven that stocks which carry the promise of very high returns with a small probability (so called “lottery stocks”) are systematically overpriced relative to their fair value1.

Source: D. Kahnemann, Fast and Slow Thinking

Insurance-Linked Securities (Cat Bonds)

In insurance, prices are much closer to their associated probability-weighted loss than is the case for lotteries, thanks to competition, and because buyers are probably more financially sophisticated than those who buy lottery tickets. Insurance serves a useful function in society by enabling economic subjects – companies as well as individuals – to relieve themselves of risks that are too big to bear. However, the insurance industry has a problem with natural catastrophes. If a large number of policy holders in a certain area suddenly have a claim based on the same event, insurers can quickly be overwhelmed. The first such insured event occurred in 1842, when the city of Hamburg burned to the ground. In its wake, that single fire bankrupted what was then the entire German insurance industry, which subsequently led to the foundation of Cologne Re. The episode gave birth to a whole new industry, called reinsurance, which is tasked with protecting primary insurance companies from the existential risk of being wiped out by very large natural catastrophes.

A reinsurance contract essentially specifies that in return for upfront premium payments, the buyer (cedent) of the policy will not bear losses in excess of a certain threshold from a predefined event (e.g. an earthquake). Reinsurers will then engage in several strategies to avoid being bankrupted themselves by these events:

1) Firstly, Reinsurers need to have deep pockets. Market-leading reinsurance companies like Munich Re, Swiss Re, Berkshire Hathaway or Lloyds are recognized as some of the best capitalized players on the planet.

2) Secondly, they diversify. By insuring different types of catastrophes in different parts of the world, they ensure that no single event – like a fire in Hamburg – can wipe them out.

3) Third, they operate on a global scale. This is a necessity because it enables point two above, diversification.

4) Fourth and last, as the value of insured sums has risen dramatically, reinsurers have engaged with public capital markets. As Michael Lewis described so well in his 2007 article “In Nature’s Casino”2, the high demand for insurance naturally leads to ever higher losses in the event of a single hurricane or earthquake. And the best way to transfer that risk is by engaging capital markets. After all, even the largest loss ever caused by a natural event – Hurricanes Katrina (2005) is estimated to have caused an economic loss of $125 billion, $80 billion of which was insured – represents an amount equal to just 0.10%3 of the global stock market capitalisation.

And that is why, in the last 15 years, participating in reinsurance markets has become a source of investment returns. The corresponding asset class is called insurance-linked securities, or more simply “Catastrophe Bonds”. According to industry sources, the total outstanding volume amounts to $42 billion as of September 2020.

The Returns

At this point, dear investors, you may still ask yourself “what’s in it for me?”. So let’s check that there is sufficient money to be made, and then go back and examine the nature of the risk in some detail.

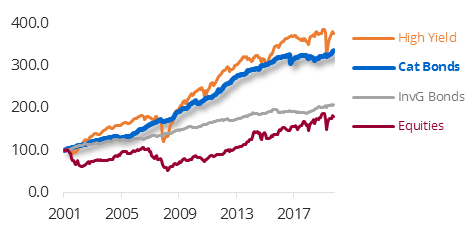

On the question of returns, there is good news in that at least historically, cat bonds have delivered returns in excess of global equities AND global bonds. Exhibit 2 compares the result of a hypothetical investment of the de facto asset class benchmark, the Swiss Re Global Cat Bond Index4, with both global equities as measured by the MSCI World and global bonds (Barclays Global Aggregate, Euro-Hedged). As you can see, the results were pleasing, as cat bonds have delivered superior returns, comparable to those of high yield bonds.

Sources: Bloomberg, Lansdowne Partners Austria

Three caveats apply, however: First, you cannot buy an index. There are no ETFs available, and as with high yield bonds, the average manager trails the benchmark even before cost and fees are taken into consideration. Second, in the early days of cat bond investing, only a few specialised hedge funds were providing capital, so we have to ask whether it is reasonable to expect the same returns going forward that these pioneers were able to capture. Third, the index has plateaued between 2017 and 2020, and only recently broken out to new highs. We need to understand why this has happened, and what might be in store during the coming years.

To begin, in the context of current EU regulations, only the most liquid sub-segment of the insurance-linked market is investable by UCITS-funds. The securities under consideration are legally structured as bonds. They pay a coupon, which is fixed at the time of issuance and which fluctuates depending on the nature of the risks underlying each specific transaction. Historically, we have observed coupons between 5% and 10% above LIBOR (cat bonds are frequently structured as floating-rate securities). At the end of the bond’s life – usually 2-3 years – the investor gets his money back UNLESS a catastrophic event (as specified by the prospectus) has occurred. In that case, the bond is deemed to have defaulted, and investors lose up to a pre-specified maximum part of their principal, depending on the size of the reinsured losses.

The nature of the proposition is that at the time of an investment, these losses can only be estimated based on historical observations, aided by sophisticated computer models. These models assess the likelihood of events capable of triggering a default: how probable is it, for example, that a hurricane of a certain strength will form? How probable that it makes landfall? … that it makes that landfall in a densely populated area? .. and so on. The result is a forward-looking estimation of probability-weighted losses. On the other side, the coupon is determined – as is customary in capital markets – by supply and demand at the time the bond is issued. For the investment to “work” for us as fund investors, the coupon must be higher than the probability-weighted loss. Given the many imponderables, we would even argue that it should be comfortably higher.

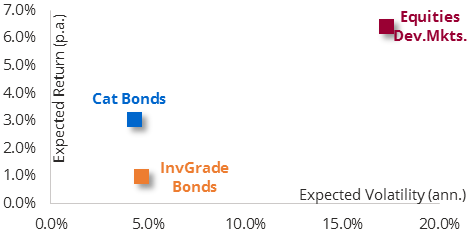

Based on the best assessment we can make, that is indeed the case. Moreover, in comparing the spread between the coupon and losses with its history, we conclude that the “valuation” of cat bonds is at historically average levels. By combining that spread with today’s outlook for interest rates and hedging costs, we come up with an estimate of a ~3.0% expected annual return from the global cat bond universe.

The Case for Cat Bonds

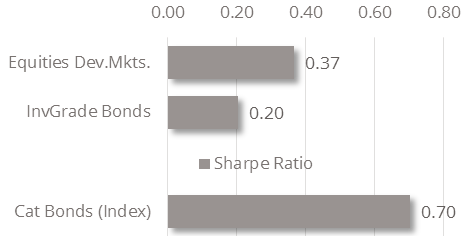

In the context of today’s capital markets, a prospective return of 3.0% is very attractive, especially in combination with the low volatility the asset class has exhibited over time. It becomes more attractive still when we consider that the returns from insurance-linked investing are essentially uncorrelated to the rest of the portfolio. Let’s remind ourselves that most of an investor’s portfolio risk is exposed to the economic cycle, and even the broadest possible geographic spreading-out of that risk could not insulate us from the losses of 2020. Cat bonds, on the other side, are fundamentally driven by weather patterns and/or seismic developments, neither of which has anything to do with the economy. Logically therefore, the correlation to equity returns is low, and so is the correlation with investment grade bonds. And we expect it to stay low, because there is no economic linkage. Exhibit 3 shows the (raw) Sharpe Ratios, and an additional risk-versus-return comparison is provided in Exhibit 4.

The case is clear: Insurance-linked bonds truly are a great addition to any multi-asset portfolio!

Source: Lansdowne Partners Austria

Source: Lansdowne Partners Austria

The Disadvantages

We now turn to what prevents us from investing even more, and we begin in the year 2017. On August 30th, a hurricane named Irma formed near the Cape Verde islands. It quickly gathered strength and, between September 5th and September 13th caused total losses of about $77 billion across a number of Caribbean islands and the mainland US. It caused 15 cat bonds to default, and partial losses to several other bond issues. The event caused the Swiss Re index to drop by 15%, practically overnight. Some funds with large exposures lost significantly more. It was the largest ever drawdown for the asset class, and recovery was slow, especially because 2017 saw several other events – earthquakes in Mexico, hurricanes Harvey and Maria, and record-breaking wildfires in California. Today, cumulative insurance industry losses from the events of 2017 are estimated to have been $140 billion. It can be said that 2017 was the equivalent of Lehman Brothers for the reinsurance industry.

The episode illustrates that no amount of modelling can predict a single natural disaster. In the end, the impact from 2017 was so severe that it took the Swiss Re index a total of 128 weeks (until February 2020) to fully recover from just one week of losses.

It is interesting to note that a lack of investor discipline may have contributed to the severity of losses. An examination of history confirms that the spread between the average coupon and expected losses had reached record low levels of around 3.0% in the years leading up to 2017, after the market’s size nearly doubled between 2010 and 2016 and investors eagerly participated. Later on – especially after a disappointing year 2018 and first half of 2019 – disappointment set in and led many to move on. Ironically, at that stage, pricing improved.

Conclusion

Our analysis of the insurance-linked market leads us to maintain an overweight position in the asset class. While we cannot foresee single catastrophes, we do observe that the insurance industry overall is short of capital6, and will in all likelihood continue to use the capital market to outsource risk. This means that essentially, the power has switched from the parties who supply risk to the takers of risk. The capital providers are now in control. This is not just good news for coupons; investors will also be able to push for tighter terms & conditions and better collateral release, leading to improved profitability of cat bond investments.

Irrespective of these developments, there will without doubt be further catastrophes, leading to occasional losses for investors. And here we return to exhibit 1. Investors will generally pay a great amount of respect to those rare losses for the simple reason that human nature leads them to over-estimate their subjective probability. Based on the science of behavioural finance therefore, these observations suggest that a healthy risk premium will be available in insurance-linked securities for some time to come.

Source: D. Kahnemann, Fast and Slow Thinking

We will nonetheless continue to monitor market conditions, but have a positive outlook for the foreseeable future.

1See, for example, „Do Investors Overpay for Stocks with Lottery-Like Payoffs?“ by Bjorn Eraker and Mark Ready, University of Wisconsin,

2Full article see here: https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/26/magazine/26neworleans-t.html

3Sources: World Federation of Exchanges

4Because Swiss Re provides only a US Dollar Index, we manually calculate the cost of hedging month by month and subtract it in order to arrive at the time series shown in the chart.

5Based on LPA Capital Market Projections as of 31/07/2020

6Insurance executives speak of a „hard market”, a view that was confirmed by Munich Re at a recent conference in Baden-Baden.

Martin Friedrich is portfolio manager of the Lansdowne Endowment Fund and Head of Research. He joined Lansdowne Partners Austria in January 2019 from HQ Trust, one of the largest independent multi-family offices in Germany. Mr. Friedrich had been employed there since 2009, most recently as Head of Capital Markets Research and Co-Chief Investment Officer. Additionally, he managed client portfolios and was responsible for the investment process of LIQID, a fintech company in Berlin.

Link to Lansdowne Partners Austria GmbH: https://www.lansdownepartners.com/austria

Related Interviews:

- Family Offices, Cat Bonds, Fund Selection & “In Nature’s Casino” (Interview – Martin Friedrich, Lansdowne Partners Austria GmbH)

- Family Offices, Think Tanks, Economics & “Manias, Panics, and Crashes” (Interview – Martin Friedrich, Lansdowne Partners Austria GmbH)

- Family Offices, Manager Selection, Incubators & “Evolution instead of Revolution” (Interview – Martin Friedrich, Lansdowne Partners Austria GmbH)

- Family Offices, Incubators, Property direct investments versus REITs? (Interview, Martin Friedrich, Lansdowne Partners Austria GmbH)

- Stock Valuation, Corona & “Horror Movies” (Interview, Martin Friedrich, Lansdowne Partners Austria GmbH)

- Family Offices, Strategic Asset Allocation & Asset Manager Selection (Interview – Martin Friedrich, Lansdowne Partners Austria GmbH)

5 thoughts on “FUND BOUTIQUES & PRIVATE LABEL FUNDS: Behavioural Finance & Cat Bonds (Martin Friedrich, Lansdowne Partners Austria GmbH)”