Report on the Forum Bundesbank event at the head office of the Deutsche Bundesbank in North Rhine-Westphalia on 16 November 2023

The United Kingdom (UK) finally left the European Union (EU) at the end of the 11-month transition period on 1 January 2021. Some observers predicted difficult times for the British economy in the run-up to this and forecast a high migration of jobs from London as a financial centre to the EU, for example to Frankfurt and Paris. Has this happened? How has the British economy developed since then and what are the future prospects for the British economic model post-Brexit and the important financial centre of London?

Johannes Gerling, representative of the Deutsche Bundesbank in London, addressed these and other questions in his presentation at the Deutsche Bundesbank’s head office in North Rhine-Westphalia on 16 November 2023. There is great interest in the topic, as developments in the UK and London are of great importance both for the financial centre of Frankfurt and for the North Rhine-Westphalian economy.

Structure of the British economy and the role of the financial sector

The structures of the British and German economies differ significantly. In order to better understand current developments, some background information should be provided first:

– The British economy in comparison1:

UK Germany (DEU)

Population: 66.97 million 84.08 million

GDP $3.07 trillion $4.07 trillion

GDP per capita $45,850 $48,433

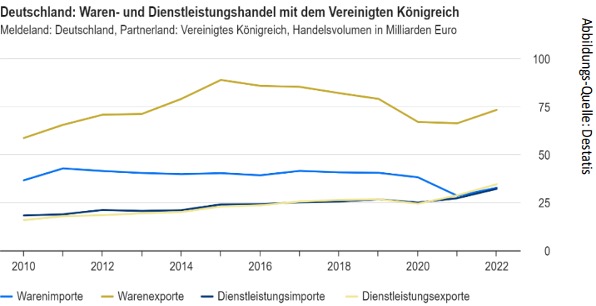

- The British economy is significantly less export-oriented than the German economy (GBR approx. 31 %, DEU approx. 48 %)2 and strongly characterised by the service sector (GBR approx. 80 %, DEU approx. 70 %)3 – this is particularly evident in foreign trade (DEU: clear dominance of goods exports; GBR: almost balanced ratio between goods and service exports)

- The financial sector is of particular importance to the UK economy (share of value added approx. 8% (e.g. DEU: approx. 4%), jobs in the financial sector approx. 1.1 million, 405 thousand of which are in London).

- The EU is by far the most important trading partner for the UK, although its share has been declining for some time (exports 42%, imports 50% of total trade in 2022). A deficit in bilateral trade in goods with the EU of £117 billion contrasts with a surplus of £25 billion in trade in services.

New framework for EU trade relations

Two agreements form the essential basis for new relations between Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the EU:

- The Withdrawal Agreement primarily regulates the rights and obligations arising from the UK’s long-standing membership of the EU, including payments to the EU budget. The Northern Ireland Protocol as part of the agreement prevents a “hard border” between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, but at the same time introduced a new customs border between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The agreement came into force on 1 February 2020 and provided for a transition period for the UK to remain in the EU single market until the end of 2020.

- The trade and cooperation agreement primarily regulates trade relations and fishing quotas, but also cooperation in areas such as law enforcement, justice and research. It was signed on 24 December 2020 and came into force on 1 January 2021. It enables the largely duty-free movement of goods, but does not prevent the creation of new, non-tariff trade barriers (customs documents, product safety certificates, etc.). The free movement of persons between the EU and the UK no longer exists.

Similar to other modern free trade agreements, the trade and cooperation agreement essentially only contains very general agreements on trade in services that hardly go beyond the level of the corresponding WTO standards (World Trade Organisation). In the area of financial services, the UK is basically treated like any other third country. A corresponding equivalence decision by the EU, which would form the basis for EU-wide market access, currently only exists in the area of central counterparties (CCPs)4. The financial market dialogue newly established between the EU and the UK does not conceptually go beyond the EU’s exchange formats with the USA and Japan, among others, and does not decide on market access issues.

After Brexit was finalised, relations were initially severely strained as the British government refused to implement the Northern Ireland Protocol agreed with the EU, including new customs controls between Great Britain and Northern Ireland, in accordance with the treaty. An important step towards normalising relations between the EU and Great Britain is the “Windsor Framework” from February 2023, as it addresses some of the key issues surrounding the Northern Ireland Protocol:

- Trade and customs issues:

Establishment of so-called “Green Lanes” for goods that remain in Northern Ireland (quasi abolition of customs controls), acceptance of GBR standards for food in Northern Ireland by the EU (must bear “not for EU” labelling). Simplifications also for medicines. Parcels to friends and family and from online shops no longer require customs documents. Greatly simplified entry for pets. Specific customs problems for steel are eliminated. - Subsidies and VAT:

Restriction of Brussels’ right to have a say on subsidies affecting Northern Ireland. Extensive exemption of Northern Ireland from EU VAT rules. - Sovereignty and institutions:

“Stormont Brake” allows the UK to suspend the application of new EU internal market rules in Northern Ireland (EU can respond with “targeted remedial measures”).

There are new foundations for cross-border financial services post-Brexit:

- The implementation of Brexit on 31 December 2020 created new conditions for market access in the EU. EU-wide passporting was lost. Instead, EU equivalence decisions and a “patchwork” of national access regulations apply.

- The UK granted EU institutions a transitional period of up to three years through the “Temporary Permissions Regime” (even longer in some areas). The EU did not offer any such transitional arrangements for British institutions; these existed or exist in part at national level in the member states. In addition, far-reaching special powers were granted to the British institutions.

- In addition, far-reaching special powers were created for the British supervisory authorities (Temporary Transitional Powers) for up to three years in order to be able to flexibly counter possible frictions caused by the on-shoring5 of EU regulations.

Equivalences are the new basis for EU-wide market access, but they do not represent an equivalent replacement for the passporting rights that have been abolished. The EU regulations provide for a total of around 40 sub-areas in which EU-wide equivalence decisions can be made. However, many important regulatory areas are not covered, e.g. credit and insurance transactions or payment services. EU decisions on equivalences are the responsibility of the EU Commission and are unilateral discretionary decisions that are taken in accordance with the priorities of the EU and the interests of the EU financial markets, if necessary with the involvement of the European supervisory authorities, and can be withdrawn unilaterally with a notice period of 30 days.

To date, the EU has been very reluctant to issue equivalence decisions for the UK. There is currently only one EU equivalence decision for the UK, which applies to the UK regulatory and supervisory framework for central counterparties (CCPs).

A joint declaration made by the EU and the UK at the end of 2024 together with the trade and cooperation agreement provided for the establishment of a joint forum for regulatory cooperation in the financial sector. Parts of the British tabloid press therefore expected a downstream “Brexit Deal for the City” with further decisions on EU equivalence at the beginning of 2021. In reality, however, only a framework agreement was reached on the format of a legally non-binding regulatory dialogue similar to the dialogue between the EU and the USA, which provides for an exchange on current regulatory developments, among other things. The granting of EU equivalences, on the other hand, remains a unilateral decision by the EU Commission. The first meeting of the new financial market dialogue took place on 19.10.2023.

Another contentious issue is the extensive use of UK financial market infrastructures for clearing derivatives by financial institutions based in the EU. Temporary EU equivalence for UK CCPs was initially granted until mid-2022, which was necessary to ensure financial stability. The London clearing houses LCH Clearnet and ICE Clear Europe have been categorised as “systemically important” (regulatory indicator Tier 2) by the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA). This means that they are subject to ESMA’s direct supervisory powers and the direct applicability of the European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR). The EU Commission is endeavouring to reduce the EU’s excessive dependence on third-country CCPs. The “EMIR 3.0” reform currently being negotiated in Brussels provides for further instruments to reduce existing dependencies. The future of derivatives clearing by EU institutions via UK CCPs is currently still unclear.

Brexit is already leaving its first traces in the British financial sector

London will remain an important global financial centre even after Brexit. The City is still one of the top three leading global financial centres (behind New York). However, competition from the Asian centres of Singapore, Hong Kong and Shanghai is becoming stronger. In Europe, London can build on its strengths: Language, geographical location, metropolitan area, financial expertise, global role of the law of England and Wales, attractive city. However, London’s importance for the EU is likely to continue to decline.

According to estimates, Brexit has already led to the relocation of around 7,500 jobs to the EU – and more are likely to follow. Dublin, Paris, Luxembourg, Frankfurt as a banking centre and Amsterdam in particular are benefiting from relocations. To a lesser extent, there are also new branches of EU institutions in the UK.

Brexit has also led to the relocation of financial assets totalling more than £1.3 trillion. With the completion of Brexit at the beginning of 2021, trading in European equities has largely left London and Amsterdam has become the most important European equity trading centre. Derivatives trading has also seen a significant migration of trading volumes from London to trading centres in the EU and the US.

Starting points for strengthening London as a financial centre post-Brexit:

- Establishing London as a leading green financial centre.

- Expanding the leading role in the FinTech sector.

- Reviewing the domestic regulatory framework to ensure its attractiveness as a global financial centre.

- At the same time, utilising the new freedoms of Brexit to better adapt regulation to the needs of the domestic market.

- Financial diplomacy: Increased focus on growth markets, particularly in Asia, envisaged financial sector agreement with Switzerland and attempt to maintain British influence in international bodies.

By way of comparison, Germany is also pushing to establish itself as a sustainable financial centre and FinTech location, for example through the German financial centre initiatives (Berlin, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Munich, North Rhine-Westphalia and Stuttgart), as well as in Germany Finance, the working group of German financial centres.

Current development of the British economy

New trade barriers as a result of Brexit mean a high level of bureaucracy for exporters and importers, particularly due to customs declarations and accompanying documentation requirements. This is a particular burden for SMEs. Some are withdrawing from previous business with European partners.

Pandemic and energy price crisis overshadow the impact of Brexit. Economic development in the UK is roughly analogous to that in Germany. In other words, external factors such as the pandemic and the energy price crisis are dominating macroeconomic development (in DEU and GBR alike) and overshadowing the macroeconomic effects of Brexit. Gross domestic product also slumped significantly in the UK in 2020. The unemployment rate rose sharply in 2020/2021 and recovered in 2021/2022; it remains noticeably higher in the UK than in Germany.

Similar to the eurozone, the UK has recently been plagued by high inflation. As in the eurozone, the main drivers of inflation were disruptions to global supply chains, a sharp rise in energy prices, high private savings during the pandemic and pent-up demand for consumer goods. The situation on the labour market is tense and there is a shortage of skilled workers in many sectors. The sharp rise in inflation has prompted the Bank of England to make 14 interest rate hikes in succession between December 2021 and August 2023; at the last three meetings, the Bank of England left the base rate unchanged at 5.25 %.

However, inflation has been particularly stubborn in the UK so far. Core inflation and services inflation – as indicators of price pressure from the domestic economy – are well above the eurozone level. One important reason for this is friction on the British labour market:

The UK’s trade with the EU is suffering as a result of Brexit. Trade with Germany is also weak:

Trade with the UK has become less important for Germany. According to Destatis, the UK was still Germany’s fifth most important trading partner in goods trade in 2015 – in 2022, it was only in 11th place. However, Germany still has the third largest foreign trade surplus with the UK. However, the interpretation of the trade data is complicated by a number of special effects, including statistical ones.

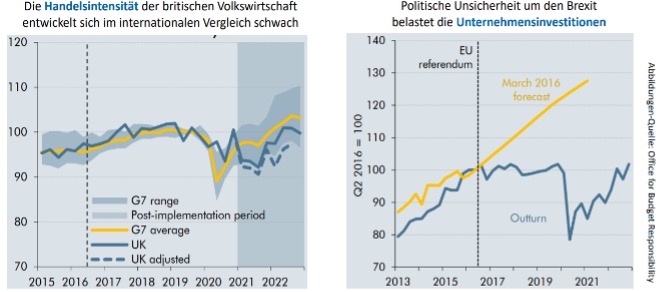

Reduced trade intensity and weak corporate investment are weighing on growth potential:

Most studies assume that Brexit will reduce the UK economy’s production potential by around 3 to 5 % in the medium term compared to where it would be without Brexit. However, quantifying the effects is not easy, partly due to methodological breaks and overlapping factors. The investment ratio, which has been low for years, is also likely to affect the prospects for competitiveness and growth in the longer term.

Expectations of “interesting trade agreements” and expansion into new markets have tended to be disappointed. New agreements that did not already exist through EU membership were mainly concluded with Japan, Australia and New Zealand; the economic impetus is manageable. Negotiations with the USA have made little progress. Relations with China have not developed as hoped. Talks are being held with India. It remains to be seen to what extent this partially deindustrialised country will succeed in rebuilding its own production capacities.

Migration to the UK remains high even after Brexit. An increasing number of non-European immigrants are entering the country via a points system for skilled labour. In view of the tight labour market, fundamental change is difficult.

Conclusion of this analysis

The consequences of the pandemic and the energy price crisis have so far overshadowed the impact of Brexit on the British economy. The adjustment of value chains and the decline in foreign trade are likely to weaken productivity growth in the medium term. A constructive economic policy, including a targeted labour market and migration policy, is likely to become even more important. Although Brexit also offers the UK opportunities, it is currently not foreseeable that these will outweigh the benefits of EU membership. London’s importance as a global financial centre is diminishing for the EU.

In an article on 25 November 2023, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) saw “A divided relationship (of the UK) to globalisation. The UK’s policy is wavering between opening up and cutting itself off. Since Brexit, trade policy has only progressed in small steps.”

However, in the longer term and in view of the geopolitical challenges, there is an opportunity to revitalise economic relations between the EU and the UK on the basis of many shared values.

1Data source: World Bank data for 2022

2Exports measured in terms of gross domestic product (GDP). Sources: Office for Northern Statistics ans Destatis; Deutsche Bundesbank; 2019 before the effects of the pandemic and the implementation of Brexit.

3Contributions to gross value added in 2019. Sources: Office for National Statistics and Destatis.

4CCPs act as financial market infrastructures between the original counterparties of a financial market transaction and replace them. They assume the default risk and thus make a significant contribution to risk management and efficiency.

5On-shoring here: short-term transfer of regulations previously governed by EU law into UK law.

(PHOTO: Kick-off Event FINANZPLATZ DEUTSCHLAND-INITIATIVE of the Börsenzeitung on 13.09.2023 with Hubertus Väth, H.-Joachim Plessentin, Hans-Jürgen Walter, Markus Hill)

Short interview (LinkedIn – “FINANZPLATZ FRANKFURT AM MAIN-GRUPPE“)

“FINANZPLATZ FRANKFURT: What challenges do you see for the Frankfurt financial center in the coming year?

Plessentin: Geopolitical developments and the economic and financial environment will continue to have an impact on Frankfurt as a financial center in 2024. Frankfurt is in competition with financial centers such as London and Paris. Strengthening the financial center and financing the sustainable, climate-neutral and digital transformation are of central importance.

FINANZPLATZ FRANKFURT: What did you take away from the Fin-Connect-NRW kick-off event on 18.12.2023?

Plessentin: The Fin-Connect-NRW financial center initiative will enter the scaling phase in 2024. The new office has presented a coherent concept for expanding the financial ecosystem and intensifying the concrete implementation of transformation processes and their financing. The new specialist working groups are also important for this process.

FINANZPLATZ FRANKFURT: Germany Finance: What impetus will be given to strengthen Germany as a financial center and transformation financing in 2024?

Plessentin: The role of spokesperson for Germany Finance, the working group of German financial centers, will rotate to Fin-Connect-NRW for one year from January. It is certainly planned that Germany Finance will commission a new study on transformation financing in 2024. The extent to which participation in international and national presentations is planned remains to be seen.

I wish my colleagues in the German financial center and the Group a good and successful 2024!”

Related Articles: